The first woollen shirts I made for our collection were designed in reference to the simple, traditional flannel shirts worn by the working class in Britain and especially in Wales. Our long tradition of flannel weaving has now dwindled now almost to nothing. In fact, when I began the process of commissioning our next run of cloth, after the closure of our last dedicated flannel mill, Melin Teifi, I hit so many barriers that I had to step back and consider my options. I felt sad about this loss and wondered why Wales has lost so much of its weaving industry. The answer to this question is long and complicated and I still don’t fully understand, but it’s because of communication technology, capitalism, developments in transportation, global economy, it’s the industrial revolution and its coal.

I have always wanted to produce clothing that connects me and my customers to the land that holds us. A modern indigenous collection if you will. But I realised that the story of who we are and the land that we live in is shaped by the stories all around us, influenced by politics, inventions, immigration - we may be an island, but we do not exist in isolation. So, with our new shirt, I decided to tell one of those stories; it is made from a very beautiful, fine and luxurious Italian wool, but in the same simple cut as our original flannel work shirts. It echoes a convergence of culture that occurred at the turn of the last century and is still visible today throughout the towns and cities of South Wales…

Cast your imagination back 250 years, to the end of the C18th. One third of the land in Wales was still unenclosed ‘common land’. Most people subsisted with a basic smallholding and simple cottage. Those who did not have their own land to work were usually engaged as farm servants or labourers, residing in the main farmhouse until married, when they would move into their own cottage, but continue to labor on the farm. Aside from land management and animal husbandry, people were occupied as thatchers, charcoal burners, clog makers, spinners, weavers and peat cutters to name a few. Then, between 1801 and 1851, the population of Wales doubled, as it did throughout Britain and Ireland. The pressure on land increased and the landless poor were forced to either make illegal enclosures on high, poor land, or seek employment in small industry. Landowners with quarries or mines often allowed the erection of cottages on their land as it enabled them to also acquire labourers for their enterprises. Other small groups of cottages would appear around sites of weaving, fishing or trade.

In the late 1830’s famine, due to terrible weather, followed by tax breaks for imported food and increased road taxes for Welsh farmers made it increasingly difficult to eke out a living.

An illustration of the Rebecca Riots in West and Mid Wales from 1839-43

Elsewhere in Britain at this time, the mechanisation of textile production and transportation was gathering speed. In the 1760’s, two spinning machines had been invented, heralding a new era for textiles, and as more mechanical inventions followed for the combing and weaving of fibre, textile production no longer relied on skilled cottagers working with spinning wheels and hand looms to create woollen cloth for export.

Factories were established, massively increasing productivity and therefor also a demand for transportation, meaning more iron and a hunger for coal.

At the time the Spinning Jenny was invented in 1760, Merthyr Tydfil was a village of about 40 cottages. By 1801, only 40 years later, Merthyr had a population of nearly 8,000 people, all employed in the production of iron.

An illustration of the early slums of Merthyr Tydfil, courtesy of the BBC

Infrastructure could in no way keep up with the growth of industry and workforce. The settlements in the valleys of South Wales became slums, with families living in single room huts only 2m x 1.5m built directly on the iron slag heaps. There were open sewers and infant mortality was extremely high.

Tip girls, working at Abergorki Colliery, Treorchy, C1880

In the decade between 1880 and 1890, over 100,000 people left their homes in rural Wales to join the frontier urban society of the industrial valleys.

It is hard to imagine swapping a life in the countryside for the squalor of a mining town, but at that time, the reality was a choice between a hard won wage or starvation.

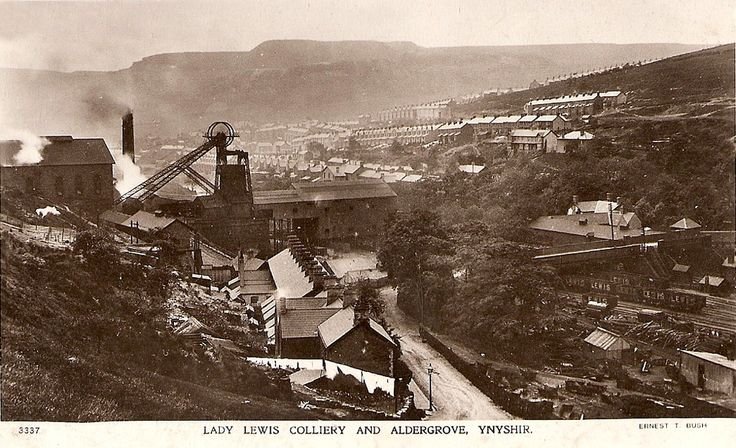

At its height, in 1913, there were 620 coal mines in Wales, employing 232,000 men, producing 57 million tonnes of coal in that year alone. Industry of this scale would never have been possible with the Welsh population alone. The immigrant workforce in the C19th to Wales consisted mostly of destitute English people, many Irish and towards the end of the century a large count of Italians.

A century of political unrest had ground out a desperate poverty in Italy. By the unification of the country in 1861, the country was still predominately rural with a large peasant class, trapped in the mezzadria (sharecropping) system with little or no opportunity to improve their lives. This resulted in a mass diaspora, with 16,000,000 Italians emigrating the country between 1880 and 1914.

A huge number of Italians sought a new life in America, but, closer to home, many were drawn to Britain by its booming economy. Initially the work was migrational, many coming to work for the summer months, often busking with street organs or selling ices to the adventurous Victorians and returning home for the winter with some money for their families. But the road was hard and long, and the opportunities in Britain were plentiful compared to the subsistence life of the rural Italian poor. By the end of the C19th over 1000 Italians had settled in Wales, many of them working at the busy ports along the south coast.

Up in to the valleys conditions had begun to improve a little with the formation of workers unions, welfare halls and parliamentary representatives. People had a little more autonomy, were managing to build homes and build community. People worshiped on Sundays, men sang in the choir and there were working mens clubs and pubs for socialising and drinking. These were not, however, acceptable places for women. Although there was no ban on women in pubs, those who were known to be seen in such establishments suffered extremely undesirable reputations.

After the Mines Act was passed in 1842, women and boys under 10 years old were no longer allowed to work underground, but it took almost 2 decades for the ban to really come into affect due to a lack of inspectors and the much lower wages that pit owners could pay women and children. Eventually women were moved up to the pit edge, where they pushed and emptied the trams of coal, breaking, cleaning and packing. They became known as the tip girls and continued to horrify society by engaging in hard, dirty ‘mens’ work. They became a tourist attraction, considered hideous and immoral, with postcards of the ‘trouser wearing hermaphrodites’ being sold as curiosities.

By 1886 Parliament announced it would create a new Mines Act to ban women from working at the collieries completely. Society believed that women should be engaged in the more appropriate sectors of household service or factory work, but those kinds of jobs were extremely scarce in Wales. A large gathering of miners was held at Temperance-hall, Tredegar. Although women were not allowed to speak, the case was put forward that without this employment many widows and unsupported women, who had worked the tips since childhood, would have no other choice but the workhouse, and that the outdoor work was far healthier and more moral than the cotton factory work that many were engaged with in the north.

So the women kept their jobs, but their own voices were still not heard in society. They continued to be paid a fraction of a mans wage, and gender segregation was entrenched.

Around this time some of the Italians that had migrated to Wales started to make their way up in to the valleys from the coast and saw an opportunity to share their own culture amongst the clustered ranks of terraced cottages.

Since the C17th coffee had become increasingly popular in Italy. The Ottoman Empire used the port of Venice to supply Europe with coffee grown in its Ethiopian plantations, so it stands to reason that it was in Venice that the first coffee houses were established. Caffè Florian was opened in 1720, and is still going to this day. At a time of political reform and new ideas about class and social boundaries, it became a meeting place for artists and writers, political thinkers and, indeed, women.

Cafe Florian, Venice

From the 1890’s onwards, Italian families began to open cafes in the new colliery towns. To begin with they sold simple meals, cigarettes, sweets and tea, sending out young Italian boys in the summer with hand carts full of ice-cream or fish and chips in the winter.

Later they acquired the newly invented steam espresso machines, bought over from Italy, and sold coffee and chocolate; small luxuries in a life of extremely hard work, and a place to gather and share ideas regardless of age, gender or class. For the first time in this new urban society, women had access to a social space where they had a voice amongst men.

The Italians worked extremely hard to build and establish their cafes in Wales, often bringing over family members or young boys from their home villages to work in their businesses. By the outbreak of WW2 there would be over 300 Italian cafes in South Wales, forming a central part of life around the mining towns of the valleys that is still present today.

Our Italian shirt is made in our home studio in mid-Wales, in a simple, comfortable style that reflects the traditional flannel work shirt, but this time in a fine and elegant cloth; a little luxury from Italy.

The cloth we have chosen is designer salvage, meaning that it is the end of multiple bolts of cloth left over after a fashion house has finished production of a line of garments. The cloth has been intercepted before reaching landfill, and made its way to our studio, so that, in our small scale way, we can turn it into beautiful clothing. You can buy our Italian Shirt HERE